Blog Layout

Latest News

Growing Up

Jun 06, 2019

from Modern Jeweler

For the high-end independent, opening more doors may be the key to greater profitability.

Posted: April 8th, 2009 09:39 AM GMT-05:00

Consolidation. It’s the byword of the 21st century jewelry industry. A drive down certain American highways, however, unveils a different picture. It’s of that trusted downtown jeweler, the mom-and-pop whose market share seemed so threatened as the 20th century came to a close. The billboards and radio ads tell you he’s now in the adjacent town as well. He’s 20 miles up the road, too, or 300 miles down, and across the state line.

And he hasn’t just expanded. As you enter the new locations, you’ll see much the same look, brands, and in-store experience that brought you to his original door.

And crucially, in the back office you’ll learn his business is defined by that same feeling of community that kept you a customer when Zales came to town. Have a kid in Little League? The new store’s manager may well be his coach. A favorite Friday night restaurant? He may have a cross-promotion going, or offer concierge service. A defining local event, business group, or charity? A treasured summer retreat or alma mater? He may be a sponsor, be on the board, be your neighbor, and if he’s not your fellow alum, he may be taking on students as summer interns.

The four multi-door retailers interviewed for this story had different goals, needs, and methods. All agree that the trick to expanding—a mixture of science, intuition, and friendly bankers—is maintaining the flagship’s premise. Think of it as globalism in miniature. The real action takes place in the backyard. Yours must be the store in its niche, no matter what (or where) that niche may be.

In the words of Craig Rottenberg, whose family is currently looking at a seventh door for Boston-area Long’s Jewelers, “We’ve evolved into a destination.” For a jeweler, that means branding, the ones you carry and/or the store itself. “I’m a believer,” says Virginia Beach’s David Nygaard, who has grown from four to 40 employees in three years of expansion, “that brands, like politics, all start local.”

MOVING ON UP

Long’s, in Massachusetts and New Hampshire. David Nygaard, one Virginia Beach door to six in the Hampton Roads market, and currently looking across the state line to North Carolina’s Chowan River area, where Nygaard has a summer property. Bernie Robbins Fine Jewelry, soon to be ten doors in the New Jersey and Philadelphia area. Ware Jewelers, Auburn, Alabama, grown from a college town staple begun by his father on a $5,000 loan 50 years ago, to four doors in the state.

They’re hardly the first retailers who’ve tried to expand. “The early eighties saw a lot of attempts,” remembers Fantasy Diamond president Louis Price, “and a lot of failures.” Over-expansion led to financial failures, errors of management or sustaining a correct price point and merchandise balance, and to loss of personal customer service. By the decade’s end, the big chains were very big, and had begun to swallow local markets. “The guys who are succeeding now,” says Price, “are more cautious. They know how to leverage their strengths—the quality of their people and the intimacy they can offer. They also tend to be going upscale as they expand.”

For expanders, upscale begins with location: the lifestyle center of the best local mall, revived downtown areas, free-standing doors. “We’re opportunity driven,” says Bernie Robbins’ Harvey Rovinsky, explaining the decision process for his 10th door, in affluent Short Hills, New Jersey—Robbins’ first with exposure to a customer base commuting to New York City rather than Philly or to the Jersey business corridors. “We know who we are: 30-plus customers at the upper financial reaches. That makes location a bit of a science, not reducible to demographics, but certainly benefiting from them.”

The Rottenbergs look at numbers, but rely on gut feeling, and a local road map, as much if not more. “We look at population and income, of course, but convenience is big. How many left turns do you have to make, for example. What’s the exposure to highways or traffic arteries?” The decision-making begins with a single imperative: find a new community. Now in two states, Long’s would have no qualms in expanding to Connecticut or Maine.

In the Hampton Roads, Virginia area, where demographics vary widely, location begins, says Nygaard, “with an identifiable pool of jewelry purchasers. But that’s not as easy as it sounds. By census data, we’re low salary. But throw in unearned income—retirees transplanting to Williamsburg—and it goes up quickly.” With each expansion, the business model, and final decision, is therefore shaped not with target numbers, brand awareness, or price point, but with market share as the matrix. “Wal-Mart is number one in the country, with a 6.2 market share. Anything above 6.5 for a given door’s locale is great, and we’ve calculated we hit it in ’05 in Virginia Beach,” the largest of Hampton Roads’ seven cities, with a population of 405,000.

“Do not,” says Craig Rottenberg, “expect immediate results. Manage the business, but also expectations. Think of it as sending a kid to college, or opening a new restaurant. The ROI’s not going to be there overnight.” As Rovinsky puts it, “This business inhales cash. With 10 doors, it’s always a challenge to be able to reinvest.”

GOOD NEIGHBORS

Risk and cost can be defrayed by relocating rather than expanding. Long’s didn’t lose a client in two moves from mall locations to single doors across the street. Six months prior, customers were given shopping bags with the new doors’ likenesses and locales. “It’s funny,” says Rottenberg, “but we had new customers in each location who weren’t aware we’d been across the street in the mall for years.” Long’s saw 25 percent price point growth a year after the moves in Peabody, and Burlington, Massachusetts. “Nordstrom is now moving into the market across the street, validating the attractiveness of each market.”

Nygaard’s expansion began in 1999 with a relocation of his mother’s former jewelry store to a free-standing door in a high-traffic center. He feels the distinction is neither affordable nor important in expanding. “Varying with the available space, local feel, the traffic flow, free-standing or in a strip mall. A more important question is who are your fellow tenants?”

“All our stores,” says Ronnie Ware, “are across from the Williams-Sonoma, the Chicos, Dillards. Or if not, they’ll come. The developer of our Montgomery door put in 36 holes of golf, then homes and shopping. That store kicked in from go.” Luxury is a condition of the leases Ware signs. “Exclusively high-end lifestyle tenants, guaranteed,” he says. “They require us not to be a credit jeweler. In Spanish Fort [Ware's most distant location, 220 miles from Auburn in a tourist destination], the developer invited us after seeing our Montgomery door, and even stipulated that if we’re not doing $2 million by our fifth year we’re able to get out of the lease. Our first year was over $1 million and we’re 90 percent up already this year.”

Space is equally crucial for expanders looking to maintain decor, layout, and shape. Nygaard’s doors tend to be wider than long—a function of general mall shape, but consonant with his thematic look. Interiors keep design consistent from carpet to woodwork to wallpaper to chandeliers. A visitor to any two doors will know they’re in David Nygaard. Two Ware’s doors are identical (“a substantial savings in architectural overhead,” he says) and the three expansions each have a domed ceiling.

Four of Robbins’ five biggest doors are all but identical, a streamlining that began with a move of the crucial Philly main line door from Ardmore to Radnor, and continuing with expansions in the Jersey towns of Marlton, Somers Point, and Short Hills.

“We spend a lot of money to maintain a uniform luxury experience,” he says. “All our floors have a seating area, a children’s area, a cappuccino area. In Short Hills, we’re establishing a customer vault, where you can store your jewelry, which we’ll clean when you take it out.”

For the Rottenbergs, shape is less crucial than size, with doors tending less to the 2,500-foot than 8,000-square-foot plan, though the burgeoning mini-chain has both. Big believers in in-store events, Long’s has had Mini-Coopers and motorcycles in its doors. “Big or small,” he says, “the look and feel is consistent. We’re classy without being stuffy. For us, that translates into open space. No in-store boutiques, though brands are welcome to put in their fixtures. But the sightlines have to be open.”

A STORE TO RUN

Do you carry branded jewelry? Are bridal diamonds loose or set? What price points can you achieve? Are you a micro-manager or a delegator? A consignment buyer, a memo man, or a believer in owning your merchandise? What do you look for when you hire? Are you year-round or seasonal? What comes first, ads or marketing? And just how close are you to your banker?

Auburn’s Ronnie Ware had never owed a cent in his life until he expanded. Rent on the flagship, a downtown fixture, had been locked in at $350 per month half a century earlier. When two strip-mall expansions ran into trouble, he was able to raise over $1 million on close-outs. “We started at 30 percent off, and were down to 70 percent by the end,” says Ware, whose easygoing manner belies the enormous amount of work and risk involved in expanding. “We just kept going as long as it wasn’t cheaper to smelt.”

The Rottenbergs bought 128-year-old Long’s as a multi-store affair. They scaled back on doors initially, then began its complex series of relocations, consolidations, and expansions a decade later. “Expansion,” Rottenberg says, “would be impossible without support from vendors and lenders.”

Nygaard and Rovinsky have very close relationships with their bankers. Nygaard’s is a customer, a friend, and advisor on business plans. Rovinsky has taken his to Vegas for JCK. “I share financial information with him in the most timely and proactive manner you could imagine.”

“For us,” says Ware, “it was our cash strength rather than a business plan that sold us to the banker. It helped us lock in a great rate on five year notes for two of the stores, and eased the line of credit we decided to go with in Montgomery.”

That cash strength, coupled with the lessons learned in closing out the two strip-mall locations, led to changes in Ware’s buying, branding, and stock balancing policies. “Some of that merchandise was two or three years old. We’re largely a consignment buyer now. I won’t even take an appointment unless it’s long-term memo.” It’s a strategy enabled by the diamond category.

“We’re not a preacher of cut,” says Ware, “though we do stress color. We’re G SI1, average sale. Everything is loose, and we offer a full range of mountings, and a jeweler in each door.”

And for branded lines? Ware carries Hearts On Fire but only in two of four doors. “If you’re not doing national advertising, we have forms and policies for how long we’ll carry on consignment. Some vendors have balked, but most folks I’ve bought from in Vegas for years stayed with us, particularly once they see that our stock balancing, which we do for ourselves now, is consistent with their goals.”

“I’m not a big believer in branded jewelry,” says Nygaard, who carries Simon G. and Hearts On Fire—brands he feels enhance his store identity. “You can very justifiably choose to go that way, but I don’t want to see the tail wagging the dog in my stores, or see my associates as clerks writing down the next order. I want to see them selling fine jewelry. For right or wrong, we chose to lead with our identity, the David Nygaard name.”

The strategy is consistent with Nygaard’s role in his communities. He’s prominent in everything from the baseball league to the local children’s hospital to regional CEO groups and mentoring programs. It extends to his marketing and advertising strategies—intensely civic-minded, and geared to the community. Diamonds accompanying the birthday cake in restaurants.

Planners advising presentation of the engagement ring. Store bags with gift certificates. Dinner at Ruth Chris, gratis with every major purchase. Nygaard has great regard for Audi’s “Key People” strategy, in which dealers provide cars to highly visible locals, and he emulates it in various ways.

All of it has grown organically from Nygaard’s initial motivation in expanding. “The first years of the decade saw jewelers losing market share,” he says. “I realized I could survive but not thrive in my current course. From the first change to the last, my goal has been single-minded: Find a platform for a branded in-store experience.”

That’s manifest when you enter a Nygaard door, from the tea service to private label diamonds. It’s clearer still in the type of personal service. Nygaard raided mall stores for associates in early expansions, banking on experience. “Some worked out, some didn’t. I created a profile of those that did, and use DISC [a business personality test] to establish two crucial criteria for successful candidates: influential and mature. Of the efficiencies that come with expansion, perhaps the greatest savings for us is in shortening the time to truly season an associate.” He encourages spontaneity above all in sales. “It’s hard to make a mistake if you’re providing a luxury experience.”

OFFICE SPACE

The four have markedly different sales training, compensation methods, and policies. Long’s, which relies heavily on research for its associate profile, has never paid commission. Rovinsky, who has a Wharton MBA in-house part-time to run sales training, has found that a continually evolving formula for compensation has been the ticket. All four stress that ownership of individual doors is crucial to a manager’s success. “It has to be their door ultimately,” says Nygaard.

Rebecca Garnick, Long’s marketing director, puts it aptly. “Think of the doors as children, each with their own personality and path to maturity.” Ware is even more succinct and hands-off. “One of the new associates in our Montgomery door was shocked to learn there was a Mr. Ware.” All hold manager’s meetings on a monthly or weekly basis, and bring associates to shows. After opening his fourth door, Ware hired an auditorium at Auburn to hold a sales training seminar.

Expansion brought a change in advertising philosophy, the obvious difference being in print and television versus billboards—a more sensible and affordable vehicle for a multi-door retailer operating along often interlocking traffic arteries. Long’s finds it can reach all its markets with a single ad in Boston Common, and sees efficiency in billboards, TV, and radio. Ware decided to abandon radio with the exception of the local sport radio call-in show. “I get so much more bang for the buck on the highways, where I have dozens going at any one time.”

The trend has been more toward marketing and public relations. Both Long’s and Robbins created in-house marketing divisions, and invest in cause or charity marketing, or event driven strategies. “There’s no easy way to quantify the results,” says Rottenberg, “but we have long been prominent sponsors of the Boston Marathon. It’s such an important event, and our participation reaches well past the local doors.” Rovinsky’s most recent coup came when Rolex brought students to his Radnor door to witness marketing in action. A second will come when Atlantic City’s minor league baseball team renames its ballpark Bernie Robbins Stadium.

As growth created new marketing and corporate responsibilities for Nygaard’s more conventional budget, he simply amended his managers’ job descriptions. One does human resources, others oversee training, recruiting, and merchandising. “I feel it enables me to offer them a career path, rather than a management or sales job. That is part of the puzzle for creating the branded in-store experience, for it truly is a platform, the base on which everything is built.”

It’s a philosophy and strategy shared by Long’s and Robbins, though both are brand believers, for marketing and merchandising. Long’s, with multiple bridal, fashion, and watch lines, regularly hosts in-store events, from David Yurman and Scott Kay to Breitling.

Robbins, whose floors are defined by its brands, has regular sales associate training from the likes of Hearts On Fire, as well as galas featuring the work and the personalities of designers like Michael Beaudry, Michael B., and Penny Preville. Most brands are global to all Long’s and Robbins doors, and Rottenberg feels it’s the single greatest efficiency expansion has brought—from pricing to making a large inventory productive across the entire company.

“Whether you’re a brand believer or not,” says Rovinsky, “the key to growth, and this really applies to single doors as much as to expansion, is the in-store experience. For us, that means comfort and luxury. Our customers come home to us. And the task, as we’ve grown, has been to achieve a seamless transition of that homecoming.”

For Ware, that homecoming can seem as seamless as watching television. “I have eight cameras in each of the stores, and I watch live feed from them all the time,” he says. In the large brick downtown building, business is good. An associate is calling from the sales floor about a 5.1 carat radiant. Ware, who bought the building when the 40-year lease his father signed expired, will be tearing the old flagship down in the next two or three years. “It’s kind of a white elephant. Time for a new look.”

And that look? “Not entirely sure,” he says. “But I wouldn’t be surprised if it doesn’t look a whole lot like the Montgomery and Spanish Fort doors.”

original story in ModernJeweler

Share

Tweet

Share

Mail

By Eileen McClelland

•

14 Jun, 2019

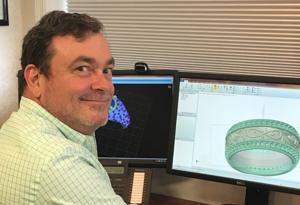

David Nygaard’s 2018 win of a Virginia Beach City Council seat represented the closest race ever in the city’s history. He won by 163 votes, a margin so slim it triggered a recount. It also represented a new direction after Nygaard had a heart attack two years ago. “I coded in the ambulance and decided, after a time of reflection, that I wanted to have a greater purpose, and I’ve always been passionate about issues and politics,” he says. “I want to spend the last years of my life on social justice.” He had hoped to run for a U.S. Congress seat, but when he didn’t qualify for the primary ballot, he shifted his focus to city council, running as a Democrat, another change. The final straw for his conversion from Republican to Democrat came with President Donald Trump’s tax bill, which Nygaard says hurt small businesses and people who were already struggling economically. He also sought to live a more authentic personal life, and so he publicly came out as gay. It’s just the latest chapter in the life of a jeweler that has taken a roller-coaster route in the past decade. In 2008, Nygaard had already been a public figure in Virginia Beach, running a high profile multi-million dollar business. So when the bank seized his home and his seven jewelry stores, along with his inventory, it was big news in the community. He also went through a difficult divorce at the time. But because he was well regarded, his fall from grace wasn’t as debilitating as it might have been. “Because we did a lot of charitable work in the community, a lot of people supported us,” he recalls. “The local media for the most part was supportive and helpful. And most customers were, too.” “You have to be upfront and own whatever problems you bring to the table,” Nygaard says. “One of the first things we did was work to protect the interests of our clients.” He refused to turn over any inventory belonging to his clients, if it had been paid for or if it was in his possession for repair. “We stood firm when they demanded customers’ items.” He brought those items to the one store he was able to reopen and gave refunds to anyone who was unhappy. “Things we were able to deliver, we delivered,” he says. “We took care of our responsibility and they supported us.” The next thing he did was devise a new business model. “When the inventory was seized, all I had was two software keys of Matrix and some old brass and glass samples, and I used those two pieces to create a new business model. I rebuilt a supply chain, and in some cases, we were able to work on the relationships with the same suppliers to do business again.” Nygaard, who has an MBA and is also a certified gemologist appraiser, rebuilt his local reputation with one custom job after another and specialized in engagement rings, using 3D printing and CAD modeling.

06 Jun, 2019

Before the Great Recession had even started, jeweler David Nygaard knew his business wasn't working. Even though he had several bench jewelers on staff to do repairs and custom design, and he himself was a designer, his days had become focused entirely on one goal: To promote the branded lines he kept in stock. Those lines had required a big investment-too big to be profitable, it was turning out-and he struggled everyday to move them at his seven stores in southeastern Virginia. He needed a new way to do business he knew that too. So he decided to try using prototype samples. Known throughout the industry as "brass-and-glass," these samples would allow him to test-drive style variations with his customers, without having to carry live inventory in all of his stores. He first asked two of his vendors to create some samples based on their bestsellers, but they were very skeptical and resisted. So instead, Nygaard himself chose two of his most popular styles and had versions made in silver, each one customized to reflect local customers' preferences (as well as protect him from copyright issues). Each prototype could then be further customized according to a customer's tastes – including the choice of metal, gemstone, side stones, and setting. In this way, the cost of precious metals and gems to make the pieces could be deferred until he actually had an order in hand. "We reduced the number of live versions of those styles to just two or three, and replaced [what we removed] with prototypes in each of our seven stores," he remembers. "I discovered that we were able to save our company about $300,000 in inventory holdings for just those two styles". Even more important to Nygaard was that his customers could now have fun and participate interactively in choosing their jewelry. Prototypes mean they could look over a range of rings (instead of just inspecting one at a time for security reasons) and pick them up and touch them freely. A long- time fan and personal friend of business expert Joe Pine, author of The Experience Economy and Mass Customization, Nygaard had taken to heart Pine's exhortation to retailers to transform their businesses into ones that entertained and delighted customers, giving them an experience they'd never forget." Pine pointed out that in order to transform a product [like jewelry] into a service, one simply needed to customize it for the user," says Nygaard. "To turn a service into an experience, however, one had to 'stage' the service into something memorable, engaging, and educational. Jewelers have a unique opportunity to provide truly transformational experience we have the ability to help clients become who they really want to be with a customized purchase." Nygaard developed more prototypes, and was encouraging his sales team to be open to this new idea "they were as resistant as the suppliers had been"-when the downturn hit. A bank called his loan at the beginning of the recession, and despite his good credit history, Nygaard lost all but one of his seven locations, his live inventory, and his employees. All he had left in his Chesapeake, Virginia, store were his prototype samples-and a license for Gemvision's Matrix CAD System that his bench jewelers had used. And that system would help Nygaard to create a new business, one based primarily on virtual inventory and mass customization. Virtual Reality Nygaard had for years been intrigued by the pioneering work of Greg Stopka, owner of JewelSmiths in Pleasant Hill, California, who had long ago given up his investment in live inventory. Instead, Stopka had chosen a digital alternative. He had installed computers throughout his store, on which he could show his customers a range of CAD renderings-renderings that could often be modified right in front of them. No inventory, no unsold items gathering dust. Just customers able to get what they wanted. "Greg's model seemed to address the whole problem of unsold inventory and low stock turn, which is the bane of the industry," says Nygaard. "In addition, I was noticing that even the most successful designer lines I stocked needed slight modifications to satisfy my customers' desires for personalization. Yet most designers are not set up to easily modify their designs. It would take them a long time to make the customized version-and then I was still left with the original live piece, which I still hadn't sold! But I knew that I wasn't capable of customizing jewelry either, because I wasn't CAD – or bench – trained, even though I am a designer and a gemologist." So Nygaard took that Matrix license and set out to learn CAD designing for himself, because he knew that was the key to Stopka's virtual inventory model. "I had essentially viewed CAD as just a way for my bench jewelers to move beyond hand carved waxes [when they did custom work]," says Nygaard. "Learning CAD helped me to see its potential as another very powerful tool-in addition to prototypes-to help create that customizing experience for my clients." It took Nygaard about four months to learn the essentials of CAD and to be able to handle basic ring designs. As his skills increased, he began to amass a library of styles. If he had prototypes that were particularly strong sellers, he created digital versions that he could show to customers and manipulate. And he used his prototypes to help customers learn about styles and proportion. Nygaard recognized early on that people had as much trouble articulating what they wanted as he had trying to predict it with live inventory. Clients also struggled to translate big images on a computer screen to tiny life-size pieces until they saw a similar prototype. "I also redesigned the store by removing unnecessary showcases and adding more comfortable seating and a working desk where I could do custom design directly with clients – like an office-type setting," he says. When he had seven stores, he had spent more time on management and less time on the selling floor. Now Nygaard was back to designing jewelry, working directly with customers one-on-one and liking it. When he sold a customized version of a design, he used a number of subcontractors to "clean up" his self-admitted newbie's efforts in CAD, make the models, cast them, set the stones, add personalized engravings (where needed), and finish them. When the bead bracelet craze took off, Nygaard found another way to offer customers an inexpensive customizing experience: He used his CAD program to create a bead collection that was localized to his area. A popular East Coast historic and seashore destination, Chesapeake [Virginia] and the surrounding region offered lots of opportunities for nautical, flora, fauna, and other motifs that customers could buy as vacation souvenirs. The customized beads, made for him by his subcontractors, fit on all the popular bracelet systems, such as Pandora, Chamilia, and Troll Beads. If customers didn't yet have a bracelet system from a branded line, he could help them there, too. He sourced bracelets as well as other beads, from Silverado Designer Beads by Argenti Oro, a bead line made from Murano glass, silver, and 14k gold. Nygaard liked his new business model, selling his beads and virtual designs, doing some custom CAD work for those customers who required it. But he wanted efficiency, too, and he began to see the flaws in working with only his own designs, which then required many different individual subcontractors to make and finish. "Not every service could do every aspect of a job – and because I don't do any of it beyond the design, my virtual inventory model was turning out to involve a lot of coordination and time." He also wanted to have more of a selection of designs to show his customers, beyond his own creations. He knew there were very successful bench-trained jewelers, like Stopka, who worked efficiently on the complete in-store custom-design experience. But he wanted to explore what was available beyond his doors. What he found took him to the next stage of his business- building journey. Custom en Masse In 2009, two of Nygaard's vendors, [one a manufacturer and distributor of jewelry and jewelry-related products and the other a well known CAD software company] partnered on introducing a mass-customization, virtual-inventory program. It is a countertop computerized custom-design system, which enables jewelers to work with clients to customize designs on screen from a starting point inventory; those designs were then turned into finished pieces by the distributor typically within eight to 10 days. As soon as he heard about it Nygaard thought it might help to reduce his reliance on subcontractors, while at the same time increasing his selection without expanding inventory. And when he became so engrossed in playing an early version of the program that he missed a connecting fight at an airport, he was hooked. Though he continued to create his own custom designs and use his network of subcontractors, Nygaard was among the first purchasers of a license to use the system. "It provided a nice increase in basic models I could show customers, and they loved being able to make changes on the computer screen and instantly see a realistic rendering of a ring – not a CAD drawing," he remembers. (He later added to his operation another software suite from the same group which enabled him to work with clients to find a diamond, design earrings, engrave wedding bands, and other custom tasks.) Around the same time as he purchased the software license, he also began working closely with another vendor, Overnight Mountings. Overnight was just at the beginning of its own exploration in providing prototype services, in which it creates designs, supplies silver models, and creates finished pieces for jewelers. Nygaard also ultimately incorporated prototype programs from Unique Settings of New York and Gabriel & Co. He now had an abundance of designs to show customers – without the need for additional subcontractors. His mass customization model was complete. Mass Success Nygaard puts all of the elements of that model to good use. When a customer comes in, Nygaard does what every good jeweler should: He listens. As the customer begins explaining interests and needs, the jeweler formulates a plan. With some clients, their specific requests will indicate to Nygaard that they need the "from scratch" custom experience, and they get to work on an original design, which he'll complete in CAD and send to his subcontractors. Turnaround time for this method is usually three to four weeks. Other customers may begin describing wants and needs that the jeweler knows he can fulfill quickly with that design software, his own virtual designs, or one of his prototype sample lines. Then it's a matter of figuring out which to start with: prototypes or on screen design. "Many women-though not all want to dig through case after case of styles, so I'll ask my customer if that's [her preference],"Nygaard says. "If she expresses interest, I take her over to the prototypes." Depending on the style interests she has shared, he selects from among his various sample lines to help her begin her search. "Each supplier's line has a different look, so it's great to have all of them," he says. "And the more styles you have to show a customer, the more likely you'll sell one." For customers in a hurry, he can turn around the customized designs he gets from his vendors in as little as one to two weeks. On the other hand, many men (though again, not all) love the idea of designing something using computerized technology. So after establishing that interest, Nygaard will take those customers over to his computer and they get to work designing something via the software. "But regardless of that, most people still want to hold the jewelry – and I have enough prototype styles now that I can usually show them something similar to what we're designing on screen." His new strategy of virtual inventory and mass customization has worked. "We have actually grown our business today in the Chesapeake store location above that store's highest point in 2006-7. Our sales volume is up 20 percent compared to that high point, and our margins, which were always good, have increased, too. "The jeweler does have some live inventory, he points out, which he eventually recovered from the bank that called his loan-but he uses that exclusively for those (usually male) customers who run in at the last minute and need something instantly for a special occasion. "I've [also] broken down some of the old inventory, as the price of gold has risen, or I needed the gems," he says. "But I can tell you that when it's gone, I won't be buying more." Nygaard has experienced enough success to hire two full-time and one part-time employee, all of whom are completely sold on his new selling model. "My new store manager hadn't worked in the jewelry industry before, so she wasn't tarnished with the pre-conceived idea that you could only sell live inventory. She was completely open to learning my custom systems. "As Shakespeare once said: "Oh brave new world that has such people in't!"

06 Jun, 2019

"Employment should not be a curse, it should be a blessing," said David Nygaard, founder and CEO of David Nygaard Fine Jewelers. It is with this optimistic philosophy that Nygaard and his store managers seek out the "best of the best" when it comes to their sales representatives. While some stores just read through a resume and run a credit check, the managers at David Nygaard look and wait for the right person rather than just fill a position. They've even been known to steal a few from other local jewelry stores. One who got nabbed and hired by the jewelry store is Anthony Hinds. He'd been in the jewelry business for more than 10 years when David Nygaard hired him. He calls the decision one of the best he's ever made. "It allows me to spend more time with my family," Hinds said, "I could see myself spending the rest of my career here." And that just want Nygaard wants to hear. "We find people who will create and add value," Nygaard said. "When you find good people, you find a place for them." Nygaard also openly runs his business based on his Christian faith. While employees are note required to ascribe to any particular religion for employment, one manager said the employees appreciate Nygaard's religious convictions. "We don't force it on them, but we let them know ahead of time that we're not the highest authority – we report to someone else," said Tim Birkholz, manager of Jefferson Commons location in Newport News. "They like that we have these high standards." The representatives at David Nygaard are pampered much like the customers they assist. Each location is provided with snacks, drinks and Starbucks coffee for the employees. When hired, new employees also receive a two-suit clothing allowance to get their professional wardrobe started or add to it. Additional allowances are given as bonuses as well. "New clothes can make you feel like a new person," Nygaard said. He offers professional dress workshops in addition to the clothing allowances for those employees unsure about appropriate work attire. Training and diamond certification opportunities are also offered, free of charge as long as the employee remains with the company for a year after. These workshops are part of Nygaard's philosophy of making a career out of working for his company. "I want our reps to be better off from having been here," Nygaard said. Managers participate in monthly group workshops with a retired business professor from Regent University. Nygaard is also a part of a group of Christian CEOs that combine faith and ethics in their business practices. Another aspect of employment at David Nygaard that adds to relax, family atmosphere is the solid hourly pay – employees are not paid on commission. Performance is tracked and rewarded with bonuses, but paychecks are secure. "Working on commission isn't comfortable," Nygaard said. "Just because you have a bad month doesn't mean you don't make your car payment." Nygaard expresses concern and a desire to listen through his weekly "4:15 report." He asks all employees to send him a short email every Friday. If they have complaints, suggestions or kudos they can voice it straight to the CEO. "I like to hear from the grassroots," Nygaard Said. Birkholz said the 4:15 report has a positive effect on morale and team-building among the employees who feel connected to the CEO through e-mail messages and get excited when Nygaard implements one of their suggestions. Good luck trying to get a job with the successful jeweler, though. When employees sign on they usually stay. "A 50-hours work week here," Birkholz said, "is better than a 40-hour week somewhere else."

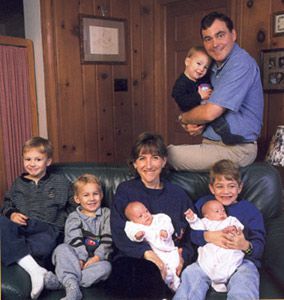

06 Jun, 2019

2005 Virginia Small Business Success Story of the Year David Nygaard Fine Jewelers (Hampton Roads Finalist) Overcoming tough odds and personal trials, jeweler builds a small business into a chain of stores. by Cindy Robinette Moshenek for Virginia Business February 2006 David Nygaard was born 42 years ago on Friday the 13th but no one meeting him today would think he was ever unlucky. The father of six is the owner of a rapidly expanding Hampton Roads jewelry-store chain. Just a few years ago, things looked bleak for Nygaard's business and his family. His single jewelry store was losing sales, and three of his children were facing life-threatening medical problems. Dealing with one of these challenges would be difficult for most people. Nygaard, however, persevered. As he and his wife saw their children through medical treatments that would include heart surgery, he took a major business risk by opening four new stores, a move that eventually increased his market share twentyfold in Virginia Beach. His accomplishments reflect his diligence in handling all of his relationships, with his family, his employees and his customers. "My success is defined by how I affect people," he says. "Everything I do reflects my values, and these values affect every facet of my life." Because of Nygaard's ability to succeed despite great obstacles, Virginia Business has named him the first recipient of the Small Business Success Story of the Year award. The magazine launched the competition to recognize the accomplishments of small business owners throughout the state. Nygaard is one of four regional finalists picked from a field of 76 nominations. The finalists were recognized at a Jan. 26 awards luncheon at the Darden Graduate School of Business Administration at the University of Virginia where Nygaard's selection as the overall winner was announced. The Virginia Business award adds to a growing list of honors the company has received in the past 12 months. The business has been named Small Business of the Year for Virginia Beach and Hampton Roads, and was cited by Inside Business as one of the best places to work in the Hampton Roads region. A native of Alexandria, Nygaard's interest in gems dates back to a rock collection he began as a child. He collected stones from the Mojave Desert while his Navy family was living in California. When he was in eighth grade, the family moved to Hampton Roads where his mother, a jewelry designer, started a business, Sandy's Touch of Gold in Virginia Beach. Nygaard joined his mother in the business after graduating from the College of William & Mary in 1986. By 1995, he had bought out her interest in the store. Three years later he renamed it David Nygaard Fine Jewelers. With the beginning of the new century, Nygaard's family and business faced severe tests. In May 2000, his newborn son, Nathaniel, developed co-arctation of the aorta, a potentially deadly defect that would require four heart surgeries over the next two and a half years. In August 2001, his wife Jan gave birth to twin girls, Aby and Aly, who were three months premature. His daughters had Twin to Twin Transfusion Syndrome, a disease of the placenta. Doctors initially gave the twins only a 10 percent chance of coming home from the hospital. Beyond that, they faced the possibility of blindness, severe retardation and other complications. During this time, gross sales at Nygaard's store were declining. They dropped 35 percent from October 2000 to September 2001 as the economic recession following the dot-com bust reduced demand for high-dollar merchandise. He was forced to cut his staff by half, from six to three. The store's sales continued at a depressed level into 2003. Nygaard, who tracked changes in the jewelry business, realized that his store was following a disturbing national trend. From 2000 to 2003, single-store businesses around the country lost 20 percent of their market share and had a declining return on assets. Nygaard managed to keep his business marginally profitable but he realized that, in its present form, "it would survive but not thrive." Nygaard credits a strong religious faith with helping him handle his simultaneous struggles at home and at work. After months of treatment in hospitals, his children were able to assume normal lives with no long-term effects. A mutual-aid group called Christian Care Medi-Share helped with medical expenses. Meanwhile, Nygaard was planning a dramatic turnaround for his business. "I wanted to build a really great business, and I realized I couldn't do that in just one store," he says. "Believing successful businessmen are not afraid to take risks, I changed my business strategy from a single 'regional' jewelry store to a multistore operation within the same media market." Nygaard came up with a detailed business plan for a small jewelry store chain and persuaded his banker, BB&T, to make a series of financial arrangements that eventually would include $300,000 in loans and $200,000 in lines of credit. In 2003, he began looking for new store locations. His second store at Greenbrier in Chesapeake opened that year, followed by the Red Mill Commons Virginia Beach location in 2004. Two additional stores, in Williamsburg and at The Town Center in Virginia Beach, opened last year, and he plans to open a sixth store in Newport News this year. The new business model has enabled the business to increase its share of the independent jewelry market in Virginia Beach from 0.8 percent in 1998 to 16 percent today. "It enabled us to provide a career path for employees and benefit from economies of scale," he says. "It is better to dare great deeds and fail than live in a gray twilight." When his current expansion plans are complete, Nygaard expects store sales to climb from $2 million at the single store to $12 million at six stores, while his staff grows from four to 40. Nygaard's CPA, Mark Bassett, says that while the jeweler takes risks, he is not reckless. His client "thinks through every aspect of his business" before making a move. "He possesses the three essential aspects of a successful businessperson: he's a great technician, a great manager and a great entrepreneur," Bassett says. "David is a well-balanced person, in my opinion." The years of struggle were not without benefits, says Nygaard. "Although these years were the most difficult imaginable, they produced happy memories and a determination to succeed. My employees and family became one and the same during this time." Tim Birkholz, manager of the company's Williamsburg store, says the ties between Nygaard's family and employees are genuine. "David's integrity as an employer comes from his realizing that the relationships we create and maintain are more important than money to us," he says. "The reason I think his business is so successful is because David is a man of high morals; he does unto others as he would have them do unto him." Nygaard's religious faith is evident. His stores, for example, are not open on Sunday. In addition, he participates in C-12, a fellowship of Christian CEOs who meet monthly to discuss ethics and business issues. The group's facilitator is Ralph Miller, a former CEO and retired business professor who also meets regularly with Nygaard's managers. These sessions, says Nygaard, help build relationships between managers and employees and, in turn, between employees and customers. Also benefitting customers is a software database Nygaard developed using a customized form of File Maker Pro. The database records customer preferences, wish lists, important events and other information. Since the database was introduced, customer returns have dropped from 1 percent of sales to 0.2 percent, and repeat customer purchases have increased by 65 percent. "We are a welcoming, nurturing, family-owned small business because of David," says Jamie Dumont, a retired police officer who manages the Red Mill Commons store. "I think he has an uncanny ability to bring out the good in people."

06 Jun, 2019

VIRGINIA BEACH, Va.— David Nygaard Fine Jewelers has been named the overall 2005 Hampton Roads Small Business of the Year by the Small Business Development Center of the Hampton Roads Chamber of Commerce. David Nygaard (BUS '03), a Regent alumnus also had his business named 2005 Virginia Beach Small Business of the Year. All competing businesses were evaluated on their performance, innovativeness, quality and leadership. During his acceptance speech, Nygaard thanked Regent's School of Business for his company's winning business model. In 1998, he bought out his mother's jewelry shop and re-branded the company, refocusing its business on fine jewelry and diamonds. Key to his business strategy is the full-service teams he has at each location. "Our main goal is to understand what our clients are aspiring to become or achieve with our product and what it will take to get them there," Nygaard said. "We want to be able to provide a bit of luxury for everyone." Nygaard's business now has four locations with two more opening soon, 24 full-time employees and pulls in increasing revenue every year. In addition to being the area's exclusive Hearts on Fire diamond retailer, Nygaard and company have also created their own designer line of diamonds and Swiss watches. Their mission is to transform the way people feel about themselves and their important relationships, with jewelry as a primary tool. A few years ago, Nygaard, one of only a dozen people nationwide who hold both certified gemologist and master gem appraiser titles, was named as one of the top 40 Hampton Roads business people under 40 years old. Nygaard's business has also been ranked the No. 7 best place to work in Hampton Roads by Inside Business this year. Nygaard takes great pride in the attention to detail required by his profession and the opportunity to impact his customers with a lifelong investment. Nygaard and his wife, Jan have six children and reside in Virginia Beach, Va. ABOUT REGENT UNIVERSITY Regent University was founded as the nation's preeminent Christian graduate university. Today, Regent offers bachelor's, master's and doctoral degrees from a Judeo-Christian perspective. With a commitment to academic excellence and innovation, the university prepares its students to become leaders to change the world. Twenty-eight graduate degree programs are offered on the Virginia Beach campus, and 13 are being offered at the Washington, D.C. campus. Students may also pursue more than 20 programs online. The eight graduate fields of study offered at Regent University include business, communication and the arts, psychology and counseling, education, government, law, organizational leadership and divinity, which also offers a Ph.D. degree in Renewal Studies. In addition, Regent now offers undergraduate degrees online—and on our campuses in Virginia Beach and Washington, D.C.—including a B.A. in Communication, a B.S. in Organizational Leadership & Management, a B.S. in Psychology, and a B.A. in Religious Studies. PR/NEWS CONTACT: BAXTER ENNIS Executive Director of Public & University Relations Phone (757) 226-4093 Fax (757) 226-4434 e-mail: bennis@regent.edu

06 Jun, 2019

David and Jan Nygaard with their six special reasons for helping Children's Hospital – from left, Calvin, 5; Lance, 3; identical twin girls, Aby and Aly, 5 months; Eric, 6; and Nathaniel 19 months, in his dad's arms. nygaard-family.jpgDavid NygaardDavid and Jan Nygaard of Virginia Beach have six children under the age of six. Three of them, Nathaniel, Aby and Aly, have special health concerns that have required the family to make frequent trips to and from Children's Hospital. The Nygaards own their own business, David Nygaard Fine Jewelers, and, in addition to work and family responsibilities, David is earning an MBA at Regent University. If there were ever a family that could legitimately plead, "Sorry, we're just too busy to help," it would be the Nygaards. But instead, they do just the opposite; they actively seek ways they can support organizations they believe in, such as Children's Hospital. Time isn't even an issue, says David Nygaard, because philanthropy means much more to him than an item on a "to-do" list. Philanthropy is an integral part of his mission in life, a thread woven into the fabric of everything he does. Last year, the Nygaards developed a fund-raising project for CHKD that shows how beautifully he is able to integrate his work talents, family concerns and philanthropic goals to the benefit of all. To honor their son Nathaniel, who is treated at Children's Hospital for a heart condition, the Nygaards created a diamond pendent in the shape of a heart. Then they donated a portion of the proceeds of every pendant they sold to CHKD. In the end, they raised enough money to purchase a new EKG machine for the cardiology clinic. It was a simple idea, born from one family's desire to express gratitude and give help. But it touched the hearts of so many others – not only those who received the pendant as a gift from a loved one, but also thousands of area children whose hearts, like Nathaniel Nygaard's, need the tender, loving care of Children's Hospital of the Kings Daughters.

05 Jun, 2019

Published: November 16, 2000 Section:VIRGINIA BEACH BEACON, page 03 Source: PAULA CROOKS Correspondent © 2000- Landmark Communications Inc. OCEANFRONT – Glasses were raised in toasts, music filled the air and employees and friends of David Nygaard celebrated another successful year in the jewelry business Nov. 4. But this party was more than an anniversary. It was also a personal celebration of Nygaard's youngest son's triumph over congenital heart disease and the official kickoff of his "Give Our Heart Away" fund-raiser for Children's Hospital of The King's Daughters, the hospital that helped save his son's life. When Nathaniel Nygaard, Jan and David Nygaard's fourth son, was born April 24, he appeared to be a normal baby. The Alanton family's ordeal began eight days later, when Jan took him to the doctor for a routine weight check. Although Nathaniel seemed healthy, pediatrician and family friend Dr. Chris Wrubel was concerned. "I had a strong feeling that something was terribly wrong with his heart," Wrubel said, and he recommended that the Nygaards take the baby immediately to CHKD for an echocardiogram. With virtually no outward symptoms, cardiologists at CHKD thought it unlikely they would find anything wrong with the baby, but the procedure confirmed Wrubel's intuition. Nathaniel had critical coarctation of the aorta in which the main artery that carries blood from the heart to the body is constricted. The condition is always fatal without medical intervention. Doctors at CHKD immediately performed closed heart surgery to expand Nathaniel's aorta, and the outlook seemed good. But in August, doctors noticed a recurrence of the condition and performed a balloon angioplasty on the 4-month-old's aorta, which had reconstricted to a fraction of its healthy width. After the ballooning, Jan contacted her childhood pediatrician, former surgeon general Dr. C. Everett Koop, who recommended that Nathaniel have a second surgery in Philadelphia to attempt to expand his aorta permanently. Doctors at CHKD concurred and referred Nathaniel to Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. The surgery, performed in October, was a success, and although he will require long-term follow-up care, Nathaniel now has a 95 percent chance that he will never need another operation. His father describes him as a "happy, easy-going baby, a real trooper" who always has a smile for his big brothers Eric, 5; Calvin, 4; and Lance, 2. David and Jan credit Wrubel and the medical team at CHKD with saving Nathaniel's life. As for Wrubel's initial intuition about the child's health, some might characterize it as a miracle. Wrubel prefers the term "miraculous intervention" to describe what he experienced. David Nygaard has his own theory: "I believe that he had a gift of knowledge and that God gave him that gift." And of the care they received at CHKD, Jan Nygaard said: "they have given us a life. We can't begin to give back to them what they have given to us." The Give Our Heart Away fund-raiser arose from that gratitude. The Nygaards' goal is to raise $10,000 for a new EKG machine through the sales of custom-designed diamond heart pendants. The white gold pendant sells for $350, of which $100 will go to CHKD. Nygaard, whose jewelry store is on Laskin Road, just east of First Colonial Road, also created a larger version of the pendant, worth $5,000 with a close-to-1-carat diamond, that he plans to raffle. Raffle tickets are $100 each. So far, the Nygaards have raised about $4,900. The CHKD staff is grateful for the fund-raising and for the increased awareness of what the hospital does. "The Nygaards are very special to us," said Carolyn Dudley, the hospital's development officer. "They are helping us put the word out in the community about what we're all about. Without this kind of support, we wouldn't be able to provide the level of care we do.

05 Jun, 2019

BATTLE OF THE BRANDS FROM GROCERY STORES TO JEWELERS, RETAILERS ARE TOUTING THEIR OWN BRANDS AND COMPETING WITH NATIONAL NAMES Published: April 30, 2000 Section: BUSINESS, page D1 Source: JENNIFER GOLDBLATT, STAFF WRITER © 2000- Landmark Communications Inc. A look inside Angela Castillo's shopping cart, as she took her maiden voyage down the aisles of Ghent's new Harris Teeter a few weeks ago, might lead one to believe that her next stop was a television commercial for the store. One loaf of Harris Teeter sandwich bread. One box of Harris Teeter sandwich bags. Four cans of Harris Teeter canned peaches. One bag of orzo under the store's newest private label – H.T. Traders. "I try to buy the store brand if it's a standard item. It's usually less expensive," Castillo said. The same is true for Anne Rowland. "I tend to buy the same stuff over and over, and I usually buy Richfood," she said. But there are exceptions. When it comes to soup and salad dressing, it's Campbell's and Ken's brands. "It's what I grew up with. It's what my mom always bought. I trust it." Though house brands have been around for decades, a new private-label push has emerged among Hampton Roads retailers, and not just in the grocery stores. It's in the glass cases of Fink's Jewelers and David Nygaard fine jewelers. And it's on the racks at Dillard's and Nordstrom. Store brands, also called private label merchandise, are anything sold under the retailer's name. These goods account for one of every five items sold in U.S. supermarkets, drug chains and mass merchandisers. Private labels are a $43 billion industry, up 5 percent over 1998, according to the Private Label Manufacturers Association, a New York City-based trade group of 3,000 manufacturers. Though private labels date back to the 19th century – when retail pioneers such as A&P carried nothing but house brands – the trend really took off in the 1970s. With the nation knee-deep in recession and inflation skyrocketing, retailers, grocers in particular, started offering generic products for customers who put low prices above quality or nutrition. The generics, best known for the trademark black-and-white labels that told little more than the name of the product, often were put into their own section of a store, away from the national brands. As the economy improved, retailers had the systems in place to develop this business and make it more lucrative. Because the grocers didn't have the expenses of national ad campaigns, they could sell the goods for less. Even at the lower costs, however, the private-label goods had a better profit margin, and they acted as advertising for the grocers. One more challenge remained. Grocers realized that "unless the quality and image of the product improved, it was going to die a slow death," said Tad Black, vice president of grocery merchandising with Farm Fresh, the Norfolk-based grocer with 36 stores. The private label manufacturers and suppliers also improved the marketing and packaging of those products. Often, private label products are manufactured by the same companies that make the goods for the national brand companies. Eventually consumers began to think of them as more than just the cheapest version on the shelf. In 1989, Loblaw, a Toronto-based chain of stores, started shipping its President's Choice premium private label brand to the United States. That move jump-started the premium private label brand business, products that have no comparable national brands or are head-and-shoulders above other store brands. Now, with the convergence of retail channels – the prevalence of grocery items in drugstores and discount department stores, for example – retailers have a chance to build store brand names as powerful as Nike, Tide and Disney. "Branding is the magic word in everybody's lexicon these days, but it's a very hard thing to do and takes a long time," cautions Paul Kelly a branding consultant in Chicago. "There's so much noise in the marketing environment that to break through and say 'I've got something new here' is hard. You've got to be very consistent with it. If it's a premium private label, you can't compromise on quality, and there's always that temptation. "A recession helps the private label business, because a lot of it's economically driven. It's kind of a testament to the power of private label that it's continued to grow" even as the economy has been so good, he said. In the supermarket industry, private labels make up about 20 percent of annual sales, up from 18.4 percent in 1994. Between 1998 and 1999, private label sales grew 3.2 percent, outpacing sales of national brands, which grew by 2.1 percent. In January, Harris Teeter introduced H.T. Traders, a premium private label of specialty items such as breadsticks and Kalamata olives, and Alfredo pesto sauce. The Charlotte, N.C.-based chain intends to expand into Tex-Mex foods, and introduce a new line of private label candy products this month. Harris Teeter has 1,356 private label products, which account for 18 to 20 percent of annual sales. Though Wal-Mart Stores Inc. touts "Brand names at Every Day Low Prices," the chain carries about 1,000 private label products. "First and foremost, we're a branded retailer, but private label is certainly a business we've seen an excellent customer response to," said John Bisio, a spokesman for the retailing giant based in Bentonville, Ark. "We don't do private label for private label's sake," he said. But they do use it for products where the national brands don't offer a lower, or "opening," price point. Wal-Mart's private lines include Great Value groceries, Equate health and beauty products and Sam's American Choice. Ol' Roy Dog Food, named after founder Sam Walton's Springer spaniel, is the best-selling dog food brand in America, Bisio said. Farm Fresh switched most of its private label brands toRichfood from Farm Fresh, when the Richmond-based wholesaler bought the grocer in 1998. However, Farm Fresh brand milk and other commodity items are still available. Soon, Farm Fresh stores will add Home Best brands, the private label health and beauty care product line of SuperValu, which acquired Richfood last year. Private label sales constitute 15 percent of Farm Fresh's annual sales. Even in departments such as meat, deli, bakery and produce, which aren't dominated by national brands, Farm Fresh is using branding to distinguish itself. The grocer carries Boar's Head meats exclusively, and its fresh bread program is sponsored by Pillsbury. Farm Fresh also promotes Dole pineapples, Tysons Chicken, Certified Angus Beef and other national brands in those departments. Beyond the grocery aisles, some local retailers have introduced house brands as a way of setting themselves apart from competitors. Marc Fink, president of Fink Jewelers, a Roanoke-based retailer with nine locations including one in MacArthur Center, trademarked his Quality Cut and Superior Cut diamonds, in 1993. "You need to separate yourself from the pack," Fink said. Fink says that sales of those diamonds make up a large percentage of total diamond sales, and estimates that he has sold more than $100 million of trademarked diamonds. Two years ago, Virginia Beach-based jeweler David Nygaard started branding watches and carrying them alongside Rolex, Chopard, Vacheron and other big names. More recently, he created three premium-cut private-label diamond brands, Star Fire, Hearts Amore and Ageless Fire. Each jeweler has agreements with suppliers to cut diamonds to certain specifications, and only those diamonds will bear the trademarked name. "It's a natural extension of the way consumers buy," said Caroline Stanley, director of marketing and communications with the Jewelers of America Inc., a trade group based in New York. "The names Mikimoto, Rolex easily connote a value when you purchase it. It seems that just now that it's being picked up at a jewelry level everywhere else." Nygaard stresses that his brand represents not just the name on the diamond. It's the live jazz music he brings into the store on weekends. It's the fresh lemonade and coffee he provides for customers. At Nordstrom, house brands are a hallmark. They make up 20 percent of annual sales for the Seattle-based department store chain, with men's dress shirts being the hottest house brands. The company has cut the number of private label brands to better position five brands that are exclusive to Nordstrom, including Classiques Entier, Halogen, Preview, Faconnable, Talora and Calloway Golf clothing. Last month, Dillard's introduced a new line of menswear designed by Daniel Cremieux. This is an exclusive agreement between Dillard's and the designer, and Dillard's is banking on $70 million in sales from the collection this year. The Cremieux line joins the host of private labels in Dillard's departments. Preston & York, Roundtree & Yorke, Copper Key and others account for about 20 percent of sales. "We're trying to fill a need," said Julie Bull, a Dillard's spokeswoman. "First, we want to be a place where customers can get quality brands. If we can't fill their needs with our branded vendor options, then we're going to come in with private label."